How do you take the temperature of a 500-pound sea cow? Destron Fearing has the answer.

If you thought wrestling with a sick yearling to get his temperature was difficult, consider what researchers go through to get a reading on a 10-foot-long, 500-pound manatee that lives in the water. Fortunately for the manatees and the researchers, innovative technology developed by a company long associated with the livestock industry, Destron Fearing, has made the job much easier.

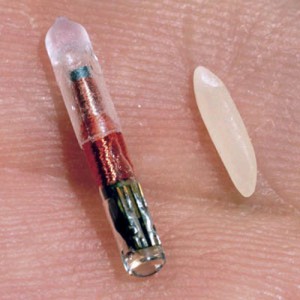

Microchips similar to those already being used in horses, llamas and alpacas have provided a better solution to managing the health of these extraordinary mammals at the Puerto Rico Manatee Conservation Center. Although their origins go back 45 million years, manatees – or sea cows – are edging closer to extinction. In an effort to preserve them for generations to come, the folks at the Manatee Center are doing their utmost to protect these gentle, plant-eating mammals. Since 1990, the Center has rescued and cared for over 26 manatees, mostly calves that were orphaned or separated from their mothers.

According to Dr. Tony Mignucci, Center’s director, who has worked with manatees for 20 years, one of the challenges his staff faces in bringing the manatees back to health is finding a way to get accurate temperature readings. Because manatees have large molars, they chew up anything put in their mouths, so getting an oral reading isn’t practical. Of course, you could always go south to get a temperature reading but that has its challenges as well, especially when manatees can weigh from 500 to 1,000 pounds and grow in length from 10 to 12 feet.

But even if you could get a reading using a soft, flexible, rectal probe, it still wouldn’t provide accurate results, explained Dr. Mignucci. “Like most marine animals, manatees can shunt blood away from certain areas, diverting it to areas of the body that need more oxygen. So, even if we were to use a 3- to 6-inch anal probe for temperature, we would not be getting a true internal temperature of the animal,” Mignucci said.

“We wrote to Destron Fearing and they kindly donated microchips and two Pocket Reader scanners for us to test in 2004,” says Dr. Mignucci. “We microchipped all the animals we had and then started taking temperatures and recording how they were doing. Now we take readings every day.”

A manatee has the chip implanted when it is still a calf and easy to handle. Each time it comes to the surface or is bottle fed, a staff member scans the Pocket Reader over the back of the manatee’s neck to get a reading. The manatee doesn’t feel a thing and the staff members don’t have to perform pro wrestling moves. The technology alleviates the stress for everyone involved, but most importantly for the manatee.

Taking temperature readings is one component of the overall health assessment of each animal with the ultimate objective of releasing the animal back into the wild. The procedure includes weaning the animals from milk to an herbivorous diet one year before their release. Three months before the big day arrives, there is a progressive acclimation to salt water. From there, the manatees are released into a sea pen with sea grasses to eat to help them become accustomed to living on their own. Following their release from the sea pen, the manatees are then monitored for one year via radio tracking. So far, three manatees have been released under this program and others are scheduled for release. Moisés, the first successful manatee to be rehabilitated, was rescued in 1992, released in 1994 and is still thriving today. Tuque, the last manatee released, lives free near the coast. At present, the Center also cares for Guacara, a Florida manatee and helps care for a manatee calf in Colombia and one in Gabon, Africa. The Center also consults on the care of Amazonian manatees in Iquitos, Peru. All are pit-tagged with Destron Fearing’s LifeChip BioThermo microchips for temperature reading.

Being able to understand and foster these great mammals is essential to their preservation. Currently, there may be as few as 5,000 manatees left in the United States and 350 in Puerto Rico. And with a slow reproductive rate – mothers only have one calf every two to five years – it is critical to do all that can be done to protect these gentle creatures of the sea. Destron Fearing is proud to play a part in this noble endeavor.